Perhaps

it was the sensationalism of the events that characterized the era, but

The Days’ Doings’ coverage also included direct encounters

with the social conflicts of the Gilded Age. As political scandals, economic

busts, devastating accidents, and corresponding hardship and social unrest

mounted, a sense of persistent crisis gripped readers. The sensational

and profane, in short, came to define many aspects of everyday life and,

while the paper’s engagement with the topical was not ubiquitous,

it was common enough to view such coverage as one aspect of The Days'

Doings' “mission.” Many of The Days’ Doings’

topical engravings made a first appearance in Frank Leslie’s

Illustrated Newspaper, but in some instances The Days' Doings

offered its readers (some of whom probably also read the Illustrated

Newspaper) additional pictures of controversial events with a different

slant—both editorially and pictorially.

In

keeping with the paper’s orientation, The Days’ Doings’

depiction of events was often filtered through a lurid lens. Coverage

of analogous social turmoil abroad, particularly the 1871 Paris Commune,

offered the editors the opportunity to both display shocking violence

and depict usually off-limits female nudity (the exception to the latter

being reproductions of fine and classical art). [11]

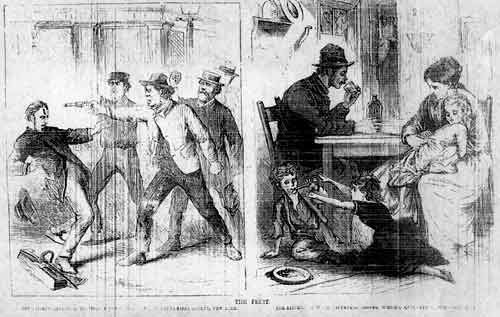

Sexuality

also imbued some of the paper’s reports on the increasing incidence

of labor militance in the streets of New York. The culmination of a strike

wave involving more than 100,000 workers demanding the eight-hour day

(the largest combined labor action to hit an American city up to that

time) elicited a full-page of engravings, the largest featuring the comely

and exotic figure of Judith Marx, emissary of the International and niece

of Karl Marx. (Figure 6) Although the accompanying description

extolled Marx’s physical beauty (albeit as an exotic: “The

Realization of an Oriental Poet’s dream”) as well as her generous

spirit, the gist of the editorial, bolstered by the illustration, denounced

her misconception that European-like exploitation characterized American

labor. The problem was epitomized in “her inflammatory harangue”—highlighted

by an oath to “’Conquer capital or die with it’”—“to

a number of ‘strikers’ who had rented a cellar in Orchard

Street . . . under the auspices of a ‘Secret Labor Society,’

known as ‘the Supreme Mechanical Order of the Sun.’”

Figure 6. “The Great Strike—The Seed and Its Fruit. The Seed. The conclave

of the strikers.—The beautiful International, Judith Marx, initiating a number

of workmen as members of ‘the Secret Order of the Sun.’” Wood engraving,

The Days’ Doings, June 29, 1872, 16.