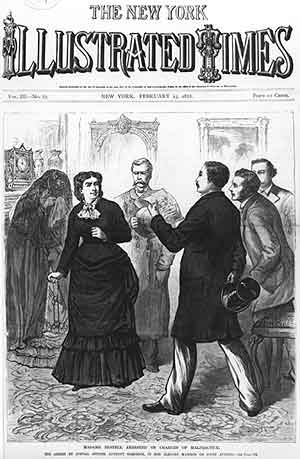

“At

last, at last!” Anthony Comstock’s diary exulted in January

1873. “Thank God!” The source of the moral crusader’s

joy was the successful indictment of influential publisher Frank Leslie

under the 1868 obscenity law. The sweeping New York State statute, promoted

by Comstock’s patron, the Young Men’s Christian Association,

covered every form of printed material and, for the first time, authorized

police search and seizure. Comstock had come into public prominence only

two months earlier for arresting the flamboyant feminist sisters Victoria

Woodhull and Tennessee Claflin for distributing their “obscene”

weekly newspaper through the mail. But he had been pursuing Leslie for

some time, and on January 14th, his quarry seemed in reach. “At

last,” his diary entry continued, “action is commenced against

this terrible curse. Now for a mighty blow for the young.”

Leslie’s

transgressions were not to be found in his popular eponymous weekly, Frank

Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, the first successful illustrated

newspaper in the United States, nor in most of his other magazines and

books. Instead, Comstock’s wrath was directed at a weekly sixteen-page

pictorial paper with the bland title of The Days’ Doings

and a more provocative policy, proclaimed on its masthead, of “Illustrating

Current Events of Romance, Police Reports, Important Trials, and Sporting

News.” Uncharacteristically, the paper carried neither Leslie’s

name nor direct evidence of his ownership, but Comstock wasn’t deceived.

Moreover, while he objected to The Days’ Doings’

illustrations of wanton and wayward women, Comstock was especially incensed

by the advertisements in the paper’s back pages. The small notebook

into which he pasted clippings of objectionable reading material included

a rash of Days’ Doings ads for abortifacients and notices

for “homosexual” illustrated books. Comstock purchased three

such books—The Secrets of Affection, The Spice of Life,

and Scenes Among the Nuns—from one of the paper’s

advertisers, W. Jones of Greenpoint, Brooklyn, as grounds for his complaint

against Leslie to the District Attorney. [1]

But

The Days’ Doings was not to loom large in the annals of

obscenity or censorship. To Comstock’s consternation, covert negotiations

between the well-connected publisher and the prosecutor led to a compromise:

Frank Leslie promised to eliminate some of his weekly's more sensational

features, and New York District Attorney Benjamin K. Phelps dropped the

charges. A dejected Comstock later left a note on his office blotter:

“This case never called for trial. Fixed in Dist. Attys office.”

Despite

Comstock’s efforts and The Days’ Doings’ notoriety,

the weekly has been mostly ignored by social and cultural historians of

the Gilded Age. And, in contrast to its inspiration and more obstreperous

(and successful) competitor, the National Police Gazette, for

all its many illustrations it has not been exploited by filmmakers or

anthologists on the lookout for evocative, not to mention copyright-free,

images depicting the theatrical, sporting, and criminal worlds.

[2]

What was

this exceedingly public and alternately shady publication? The Days’

Doings held a distinctive place among the magazines and books published

by the British immigrant engraver who was born Henry Carter but gained

fame and fortune in the United States as Frank Leslie. New York publisher

J. C. Derby remarked in his 1884 memoir that “Leslie deserves to

be called the pioneer and founder of illustrated journalism in America.

He understood what the great reading public in this country wanted, and

provided it, so that all tastes were satisfied by one or another of his

many publications." His flagship magazine, Frank Leslie’s

Illustrated Newspaper, began in 1855 and then, along with its rival

Harper’s Weekly, gained success and legitimacy covering

the Civil War. While the Illustrated Newspaper attempted to encompass

the increasingly varied post-Civil War reading public, Leslie’s

other periodicals were targeted at more specified audiences—including

German and Spanish readers, women, children, families, and religious Protestants—the

overall effect embodying the range of the diversified literary marketplace.

The aggregate circulation of all of Leslie’s weekly and monthly

magazines, according to one contemporary source, averaged about a half

million copies weekly. [3]

But,

following the lead of the antebellum sporting press—efflorescent

papers such as The Flash, The Libertine, and The

Weekly Rake—it was The Days' Doings that gleefully

embraced the less sedate manifestations of New York’s postbellum

commercial culture and brought Leslie perhaps more notoriety than even

the enterprising publisher found practical. Beginning as The Last

Sensation in 1867 and renamed in 1868, The Days' Doings'

masthead proclaimed James Watts and Company at 214 Centre Street as its

proprietor, but any alert reader could note the occasional reprinting

of engravings previously published in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper,

the signatures of regular Illustrated Newspaper artists gracing

many of its illustrations, and the ads for Leslie's publications dominating

its back pages. [4]

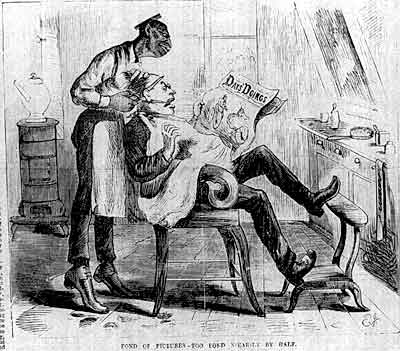

Figure 1. “Fond of pictures—Too fond nearly by half.” Wood engraving, The Days’ Doings,

June 5, 1869, 16. While employing racial stereotypes, this cartoon also indicates one

venue where readers consumed the weekly: the male preserve of a barbershop.

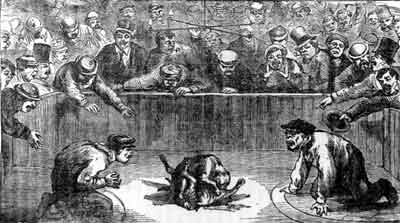

Moreover, the appearance of The Days’ Doings marked the migration of tawdry material from the pages of the Illustrated Newspaper, making the latter more suitable for the parlor table, as opposed to the barroom, barbershop, or hotel lobby, where the more brazen sporting magazine often could be found. (Figure 1) For example, after 1868 the Illustrated Newspaper ceased its regular depiction of violent crimes. The paper still was not above occasionally covering “scandalous” acts of violence, such as the 1872 murder of Wall Street speculator James Fisk Jr. by a victim of one of his swindles. But the Illustrated Newspaper’s subsequent visual reportage of murder cases offered more temperate contextual information, such as the "scene of the crime" and portraits of the protagonists, leaving The Days’ Doings to feature re-creations of fatal assaults and, its favorite, "crimes of passion," whose narratives combined titillation with cautionary morality. Similarly, illegal sports such as dog fighting and particularly bare-knuckle boxing disappeared from the Illustrated Newspaper’s pages by the early 1870s , taking up residence in The Days' Doings as the relatively more demure sibling turned to celebrating races, regattas, and baseball. (Figure 2) In short, with The Days’ Doings, Leslie could pursue a male readership with a repertoire of sex, scandal, sports, and violence that would have undermined the necessary propriety of his most valued publication.

Figure 2. “The dog pit at Kit Burns’ during a fight.” Wood engraving, The Days’ Doings,

September 26, 1868, 261.

Leslie continued to avoid direct acknowledgement of his ownership of The Day’s Doings. But by the time Comstock took action, Leslie seemed to take impudent (and, as it turned out, imprudent) pleasure in leaving obvious clues. James Watts disappeared from The Days' Doings' masthead around 1870 in tandem with the announcement of a new address at 535 Pearl Street, coincidentally and conveniently next door to Leslie's publishing house; that particular fiction was finally eliminated after Leslie's publishing operations moved to Park Place in 1878. For the close reader of the paper there also were editorial hints of the relationship almost from the start. One of The Days’ Doings’ early editorials suggested Leslie’s authorship in the very manner in which it proposed that the paper was edifying to the public, expanding the scope of the illustrated press by commemorating and uplifting the everyday through the visual arts: